The USDA announced in a press release that the Agricultural Research Service is evaluating vaccines against H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). This was confirmed on Friday 21st in an industry association webinar by a researcher at the USDA-ARS Southeastern Poultry Research Laboratory. This is probably an exercise in reinventing the wheel, given that millions of doses of vaccine are in commercial use in numerous nations. A controlled laboratory study was recently concluded at the Wageningen Institute in Holland that showed protection from two commercial HVT-vectored vaccines. The initial results provided the impetus to proceed to field trials in Holland paralleled by the intention to deploy 80 million doses in France during early summer.

The USDA announced in a press release that the Agricultural Research Service is evaluating vaccines against H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). This was confirmed on Friday 21st in an industry association webinar by a researcher at the USDA-ARS Southeastern Poultry Research Laboratory. This is probably an exercise in reinventing the wheel, given that millions of doses of vaccine are in commercial use in numerous nations. A controlled laboratory study was recently concluded at the Wageningen Institute in Holland that showed protection from two commercial HVT-vectored vaccines. The initial results provided the impetus to proceed to field trials in Holland paralleled by the intention to deploy 80 million doses in France during early summer.

The recent USDA release indicates that results will be available in May with respect to “ a single dose” program and in June for a “two-dose” regime. The USDA is evaluating two in-house developed inactivated vaccines, one based on a 2022 isolate of H5N1 derived from turkeys in Indiana. The first phase will also evaluate two commercial products available from biopharmaceutical manufacturers with two further commercial vector vaccines in June.

two commercial products available from biopharmaceutical manufacturers with two further commercial vector vaccines in June.

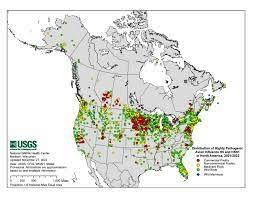

The current USDA policy is expressed in their statement “Current strategy of stamping out and eradicating HPAI continues to be the most effective strategy because it works.” The question arises as for whom and by what metric? The 2022 APHIS approach has resulted in depopulation of 58 million commercial poultry over the past 14 months. The unaffected U.S. broiler, egg-production and turkey flocks were in all probability not exposed to H5N1 virus. The recent lull in infection cannot be attributed to either increased biosecurity or stamping out of individual outbreaks. The incidence within an area is a function, of the quantum of virus shed by migratory birds and now evidently domestic free-living birds. Exposure of commercial poultry and backyard flocks occurs due to defective structural and operational biosecurity and presumed aerogenous dispersal of virus entrained on dust.

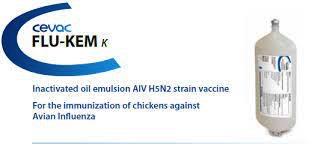

The USDA considers it would take 18 to 20 months for a vaccine to be developed that matches current viral strains. This is a questionable assumption, given the availability of commercial vaccines that appear to be effective in numerous nations against the prevailing H5N1 strain. The process of approval could be expedited given available experimental and field data.

When vaccination is approved, it will, in all probability, be permitted in regions of high poultry density that have a history of infection. Prevalence rates among migratory waterfowl along the four major Flyways will also influence decisions on vaccination. Long-lived poultry, including breeders and commercial egg flocks, should obviously be prioritized.

France has placed an initial order of 80 million doses of commercial HVT-Vectored vaccine for broilers, ducks and egg-production flocks in regions consistently affected by HPAI. Following campaigns to eradicate HPAI on an almost annual basis, authorities in France have recognized the futility of a “stamping out” policy. Strategies for vaccination have been released and the Ministry of Agriculture is awaiting comment from producers and poultry health professionals.

At present the U.S. poultry industry is divided as to the need to introduce vaccines. The overwhelming concern is the potential for the loss of broiler exports valued at $4.5 billion in 2021 and $5.2 billion in 2022. The policy of the World Organization of Animal Health allows for trade despite application of vaccination. Nations that need our leg quarters at prevailing prices would in all probability continue buying given certification of freedom from infection.

Brazil is the last major producer not to have reported HPAI to the WOAH despite the infection occurring in surrounding nations. Should this large exporter experience infection current regulation of trade will be radically changed. Importers will be more flexible with respect to restrictions. Even limited vaccination will require a radical shift in policy, perception and thinking on the part of the USDA. Perhaps this is fueling an undercurrent of denial that is expressed by invoking questions of efficacy of vaccines. The USDA has embarked on a series of industry presentations incorporating questionable economic justification of the status quo, and a component of sophistry justifying the current policy. The tenure of recent presentations is more an expression of institutional resistance to change and political considerations than by sound epidemiology and molecular biology. It is currently possible to certify that flocks contributing to export consignments are free of HPAI on the day before harvest applying PCR antigen detection. Reliance on serology is an outdated concept notwithstanding that commercially available vectored AI vaccines are DIVA compliant.

The 2022-2023 H5N1 panornitic is clearly different from previous events. The infection has become regionally and seasonal ly endemic and will reoccur. The high probability of aerogenous transmission negates the presumption that commercial flocks can be effectively protected by maintaining high levels of biosecurity. Accordingly vaccination should be considered on a controlled and limited basis to induce a high level of population immunity in areas at risk and specifically for long-lived flocks.

ly endemic and will reoccur. The high probability of aerogenous transmission negates the presumption that commercial flocks can be effectively protected by maintaining high levels of biosecurity. Accordingly vaccination should be considered on a controlled and limited basis to induce a high level of population immunity in areas at risk and specifically for long-lived flocks.

The cost of HPAI is measured by the USDA-APHIS in terms of compensation and logistics with Congress supporting the control program through the Commodity Credit Corporation, an apparently bottomless piggy bank. The presumption that this will continue is now a subject of question. A sobering reflection should be the cost to consumers of prolonged and recurrent outbreaks. Based on sale of 7.8 billion dozen eggs in 2022, the $2 per dozen increase in price attributed to HPAI cost consumers over $15 billion.

Any infection impacting a livestock segment that persists for longer than 13 months, is diagnosed in over 35 states, requires depopulation of over 58 million commercial birds without eradication and has spread to marine and terrestrial free-living and domestic mammals cannot be regarded as exotic to the U.S. The apparent lull in incident cases should provide an opportunity for reappraisal not a victory lap by USDA-APHIS.

It may be considered that “Avian influenza is the Newcastle disease of the 2020s” This equally catastrophic disease has not been eradicated although it isnot a restraint to production in the context of commercial production since the 1970s due to extensive deployment of a range of vaccines. Now is the time to rethink options and move towards integrating vaccination into control programs to limit the economic impact of HPAI.