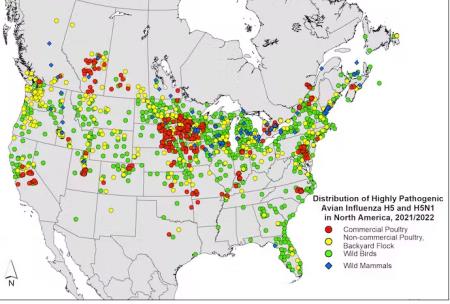

The long-awaited publication on the epidemiologic investigations carried out by USDA-APHIS, confirmed that wild migratory and possibly domestic birds were the source of HPAI H5N1 strain virus in the 2022 epornitic. The study does not specify how virus was introduced onto commercial farms, but it is possible to draw conclusions that can be used to enhance protection.

The long-awaited publication on the epidemiologic investigations carried out by USDA-APHIS, confirmed that wild migratory and possibly domestic birds were the source of HPAI H5N1 strain virus in the 2022 epornitic. The study does not specify how virus was introduced onto commercial farms, but it is possible to draw conclusions that can be used to enhance protection.

The publication* released on July 25th provided a statistical analysis of the case-control study conducted by APHIS epidemiologists. Data was obtained by telephone survey conducted from September through December 2022 on 18-case farms and 22 controls located in eight states. By early June, the winter through spring phase of the 2022 H5N1 epornitic had resulted in depletion of 31 million hens or pullets. The study did not encompass the subsequent fall phase of the 2022 outbreaks.

An interim report on epidemiologic investigations was released during the first week of March 2023. This document was inexplicably backdated to July 2022. The report provided neither conclusions nor recommendations and was the subject of a critique in EGG-NEWS on March 8th. A subsequent webinar presented preliminary findings on May 31st with expansion in the number of cases in the eventual publication. The results were both intuitive and expected but again APHIS did not provide any new recommendations other than intensification of basic and applied structural and operational biosecurity.

The publication incorporated a statistical analysis of data collected in the survey identifying factors that were in all probability associated with infection based on the magnitude of calculated odds ratios. These included: -

- Location of a case farm in an existing control zone (odds ratio 8.0)

- The presence of wild waterfowl or shore birds in proximity to the case farm prior to onset of mortality (7.6).

- Wild birds having access to feed on a farm (6.2).

- Wastewater lagoon or drainage ditch visible within 350 yards of farm (3.3).

- Mowing or bush hogging prior to onset of infection (2.6).

Given that wild birds and specifically migratory waterfowl and shore birds are known to disseminate H5N1 virus, the findings relating to their presence prior to an outbreak are not unexpected. Proximity to water or drainage ditches is also indicative of the role of free-living waterfowl in exposing commercial farms to infection. Attracting birds onto commercial farms by allowing access to feed is also self-evident. Investment in structural biosecurity and application of operational biosecurity contributed to a reduction in the probability of infection with specific reference to vehicle washing (0.3 odds ratio below unity, denoting protection). The presence of a farm gate was associated with a 0.2 odds ratio, with this factor presumably serving as a composite for structural biosecurity.

The hierarchy of biosecurity extends from conceptual biosecurity at the apex through structural and then down to operational components of biosecurity. Each is dependent on the previous level for efficacy in preventing introduction of disease. It is an unfortunate defect in conceptual biosecurity that many large integrated complexes are located in the Mississippi and Central Flyways. Large complexes that are frequently sited in close proximity to rivers and wetlands invariably predicates direct or indirect contact between migratory waterfowl and commercial flocks. Structural biosecurity requires capital expenditure and operational biosecurity is based on the provision of consumables and ongoing management with both providing variable levels of protection. Current levels of even extreme biosecurity do not address the challenge of contact between migratory waterfowl and high concentrations of commercial poultry. The emergence of clade 2.3.4.4b with wide host-species susceptibility and an apparent change in the migratory patterns of marine birds since 2021, predicate in favor of recurring infection along U.S. flyways.

The hierarchy of biosecurity extends from conceptual biosecurity at the apex through structural and then down to operational components of biosecurity. Each is dependent on the previous level for efficacy in preventing introduction of disease. It is an unfortunate defect in conceptual biosecurity that many large integrated complexes are located in the Mississippi and Central Flyways. Large complexes that are frequently sited in close proximity to rivers and wetlands invariably predicates direct or indirect contact between migratory waterfowl and commercial flocks. Structural biosecurity requires capital expenditure and operational biosecurity is based on the provision of consumables and ongoing management with both providing variable levels of protection. Current levels of even extreme biosecurity do not address the challenge of contact between migratory waterfowl and high concentrations of commercial poultry. The emergence of clade 2.3.4.4b with wide host-species susceptibility and an apparent change in the migratory patterns of marine birds since 2021, predicate in favor of recurring infection along U.S. flyways.

The major deficiency of the APHIS publication relates to a failure to identify how HPAI virus that is carried and shed by migratory waterfowl and shore birds actually entered farms. There is adequate anecdotal evidence that wind dispersal can occur over relatively short distances. It could be hypothesized that virus is shed by waterfowl attracted to retention ponds, dams and drainage areas adjacent to farms. High wind could transfer virus entrained on dust into houses containing flocks. The fact that most layer or pullet barns in the affected states, even during winter, operate with negative ventilation at high rates (1 million cubic feet per minute for 250,000 hens) would facilitate introduction of infection. Newcastle disease was shown to be wind-transmitted from affected to susceptible farms over distances of up to two miles during the Essex 1972 outbreaks in the U.K. Mowing and cultivation of fields adjacent to farms may aerosolize virus shed by free-living birds contributing to aerogenous spread. Although strict structural and operational biosecurity reduces the probability of introducing infection, it is obviously not absolute, given the number of outbreaks recorded despite documented high levels of biosecurity on some of the farms that were infected.

USDA- APHIS can be faulted for not aggressively attempting to apply known epidemiologic principles of investigation to the outbreak at an early stage in the epornitic. Experience gained from the 2015 outbreak should have resulted in preemptively establishing programs of investigation involving both field and molecular evaluation. If pre-planned, appropriately funded studies with adequate personnel could have been activated during the first quarter of 2022 during which close to 19 million hens were depleted.

The case farms ranged in size from 50,000 to 5 million hens. There are many differences in structure and operation between small contract egg supply farms and large mega-complexes with a feed mill, packing plant and service infrastructure. Combining farms with widely different capacities and facilities introduces confounding since activities and operations are different invalidating direct case-control comparisons.

The case farms ranged in size from 50,000 to 5 million hens. There are many differences in structure and operation between small contract egg supply farms and large mega-complexes with a feed mill, packing plant and service infrastructure. Combining farms with widely different capacities and facilities introduces confounding since activities and operations are different invalidating direct case-control comparisons.

An additional deficiency in the study related to the use of a 26-page questionnaire based on the 2015 investigation that was administered by telephone, in many cases months after an outbreak. Telephone surveys obviously suffer from the deficiencies of responder fatigue and recall failure. Competent investigators acquainted with U.S. egg-production practices and procedures should have been deployed to case and control farms as soon as possible after confirmation of a diagnosis in order to verify levels of biosecurity and to identify factors that may have contributed to infection. An obvious example relates to whether vehicle wash stations were effective on a specific case farm. Six months after the event, a responder will confirm that they were present but there is no indication as to their efficacy. There are many cases of malfunction of vehicle wash stations including failure due to icing during periods of low temperature, blocked nozzles or inadequate design that could confound the relevance of a factor as assessed remotely months after an outbreak.

Public funds in excess of $1 billion were incurred through activities to suppress secondary outbreaks of avian influenza including indemnity and logistic costs for depopulation, disposal and decontamination. Expenditure on personnel to conduct real-time and intensive field and laboratory epidemiologic investigations would have provided an immeasurable return by identifying both predisposing and protective factors by the end of the first quarter of 2022.

From presentations at national and regional meetings, APHIS appears to have embarked on a victory lap during early 2023 given the absence of incident outbreaks. This had little to do with the depletion of up to 44 million hens on 22 large complexes each with more than 500,000 hens but with a total of 41 commercial egg-production facilities in 11 states. The end to the epornitic can be attributed to the fact that in early 2023, wild birds were presumably no longer moving from their breeding grounds to disseminate virus. The discrepancy in incidence rates of HPAI between the first quarters of 2022 and 2023 have not apparently been investigated but are worthy of study.

The preliminary epidemiologic investigation of the 2022 epornitic, suggests aerogenous introduction of infection onto farms from migratory waterfowl. This invalidates the whack-a-mole approach by APHIS to “eradication”. The reality based on persistence of infection in Europe, Africa and in wild birds in North America suggests that H5N1 avian influenza is both seasonally and regionally endemic. This realization coupled with the possibility of aerogenous transmission over short distances presumes that tactical vaccination should be considered as an adjunct to biosecurity as an added measure of prevention.

Opponents of vaccination are primarily confined to the broiler segment, justifiably concerned over obstruction of trade. It must be remembered that the 2022 epornitic resulted in a two-fold increase in the retail price of eggs as a result of the disruption in the supply to demand equilibrium. The HPAI epornitic of 2022 cost consumers $15 billion and contributed to food inflation that became both economic and political issues transcending the narrower considerations of one sector of the U. S. poultry industry.

The authors of the USDA-APHIS study and the subsequent publication ought to be commended for their efforts. They could have made a greater and earlier contribution had they been provided with more support. The responsibility for this deficiency lies with administrators obviously lacking in knowledge and vision. The policy of APHIS during 2015 and 2022 was based on the inappropriate concept of “eradication” This resulted in simply refining the procedures and responses that were relatively ineffective in controlling the Pennsylvania 1984 outbreak.

It is hoped that APHIS recognizes the need to provide the industry with science-based recommendations to prevent HPAI. This presumes prompt collection and analysis of field data and molecular studies. HPAI will in all probability return in the fall and APHIS should be prepared to respond not only with traditional depopulation but with practical measures to reduce the economic impact. A limited study on vaccination efficiency, as conducted in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Holland would be appropriate if not already planned.

*Green, A. et al Investigation of risk factors for introduction of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus onto table egg farms in the United States, 2022: a case-control study. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. Doi: 10.3389/vets.2023.1229008