EGG-NEWS

This special edition of EGG-NEWS is circulated following the belated release by APHIS of an epidemiologic report on the 2022 HPAI epornitic. The Report is both unsatisfying in scientific content and devoid of practical recommendations to prevent infection of commercial poultry farms and complexes. Failure of APHIS to adopt a proactive approach to HPAI since the U.S. 2015 epornitic and the progress of the H5N1 strain in Europe, Asia and Africa since 2021 is evident in the Report. The Commentary below evaluates the backdated report and identifies deficiencies in conceptual planning and abrogation of responsibility by administrators of the USDA-APHIS

This special edition of EGG-NEWS is circulated following the belated release by APHIS of an epidemiologic report on the 2022 HPAI epornitic. The Report is both unsatisfying in scientific content and devoid of practical recommendations to prevent infection of commercial poultry farms and complexes. Failure of APHIS to adopt a proactive approach to HPAI since the U.S. 2015 epornitic and the progress of the H5N1 strain in Europe, Asia and Africa since 2021 is evident in the Report. The Commentary below evaluates the backdated report and identifies deficiencies in conceptual planning and abrogation of responsibility by administrators of the USDA-APHIS

For many months, EGG-WEEK has urged the USDA-APHIS to release an evaluation of epidemiologic questionnaires prepared following outbreaks of HPAI that commenced in February 2022. During the first week of March 2023, the USDA released a backdated report entitled, Epidemiologic and Other Analyses of HPAI Affected Poultry Flocks, July 2022, Interim Report.

At the outset USDA-APHIS Administrators should explain why an obviously incomplete, uncoordinated and fragmented report dealing with the data collected through May 2022 and involving various related epidemiologic studies, was released only at the beginning of March 2023.

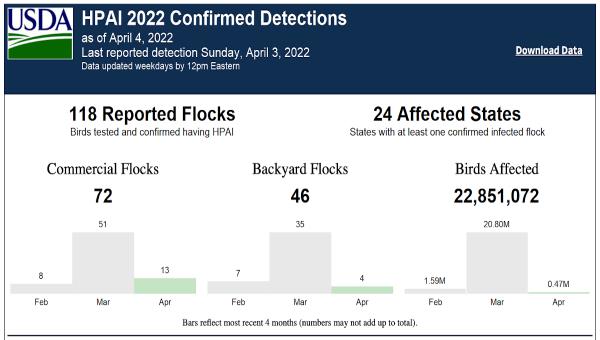

EGG-NEWS and industry associations have urged USDA-APHIS to release preliminary guidance on preventive measures based on an analysis of the epidemiologic investigations they conducted. The industry required recommendations based on completion of phylogenetic analysis and field studies including case-control comparisons. These were necessary to establish relative risk factors relating to infection among the initial twelve large egg-production complexes that were infected. These farms required depopulation of 24.8 million hens with diagnoses extending from February 22nd through April 25th and spread over seven states incorporating the Atlantic (DE, MD, PA); Mississippi, (IA, WI, NE) and Central, (UT), Flyways. A report by mid-2022 was not an unrealistic request. An initial interim report by July 2022 would have been more valuable than the anticipated comprehensive document scheduled for mid-2023 or later.

|

The most recent APHIS Report deals with the Spring wave of infection extending through May 31st. Information relating to the modes of transmission of HPAI and possible deficiencies in biosecurity would have been valuable in potentially preventing subsequent cases. Large egg complexes in Nebraska and Colorado involving 5.0 million hens were infected through mid-2022. The Fall wave involved depopulation of an additional 14.2 million hens in ten large complexes in six states extending from September through December 2022

In the event, the belated USDA-APHIS Report simply catalogued the epornitic involving cases in 35 states affecting 130 turkey farms, 55 chicken complexes, 11 duck production units and 137 backyard flocks through the end of May 2022. Total losses to date amount to approximately 44 million egg production hens, of which 95 percent were affected on 22 large complexes each holding from 0.5 million to 5.0 million hens; 9.8 million turkeys on 229 farms in seven states and 3.2 million broilers on 18 farms in seven states with 0.3 million broiler parents on 11 farms in six states. The simple listing of cases by species failed to differentiate among “chicken” cases involving a range of diverse production types and systems.

In the event, the belated USDA-APHIS Report simply catalogued the epornitic involving cases in 35 states affecting 130 turkey farms, 55 chicken complexes, 11 duck production units and 137 backyard flocks through the end of May 2022. Total losses to date amount to approximately 44 million egg production hens, of which 95 percent were affected on 22 large complexes each holding from 0.5 million to 5.0 million hens; 9.8 million turkeys on 229 farms in seven states and 3.2 million broilers on 18 farms in seven states with 0.3 million broiler parents on 11 farms in six states. The simple listing of cases by species failed to differentiate among “chicken” cases involving a range of diverse production types and systems.

In reviewing the report, including the “Initial Contact EPI Report Form”, there is not a single fact that is not generally known by poultry health professionals. There are no constructive recommendations that can be applied by a table egg producer to reduce the probability of introducing HPAI onto a complex.

The take-away messages from the report include:-

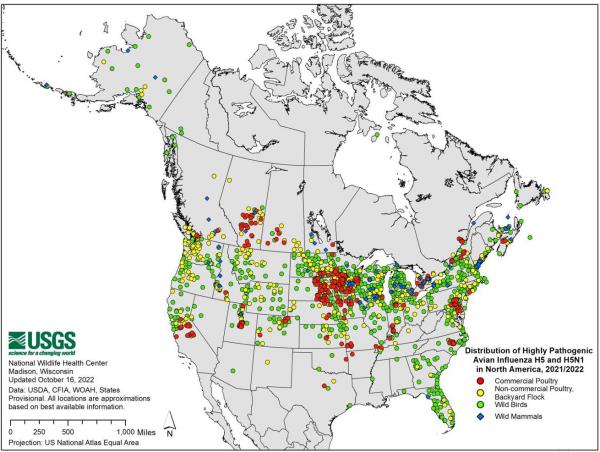

- Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza virus strain H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, expressing Eurasian genes was introduced to the U.S. as a single major introduction via the trans-Atlantic route. It is presumed but not stated in the report that diverse migratory bird species transported the virus by inter- and intra-species contact successively westward from northern Europe through Iceland, Greenland and then to Labrador with subsequent transit of the Atlantic flyway southward to Florida.

- The virus responsible for the 2022 cases and the ongoing epornitic differed from the 2015 H5N1 strain characterized as clade 2.3.4.4c.

- Of individual outbreaks investigated, 84 percent were associated with wild bird introductions based on phylogenetic analysis, an original and valuable component of the Report. This finding indicates the possibility that obvious deficiencies in biosecurity as disclosed in the 2015 U.S. epornitic were not primarily responsible for introduction of HPAI onto large in-line complexes in 2022. This presumption is based on the intensive application of structural and operational biosecurity since 2015. Required case control studies on selected in-line egg production complexes were not performed in 2022 depriving producers of counsel concerning risk factors. The Initial Contact EPI Report forms were reproductions of those used for turkey farms during the 2015 epornitic. This one-size-fits-all approach failed to consider specific routes of infection relevant to high capacity complexes essential to have identified pertinent risk factors. The questionnaires excluded metrological data preceding outbreaks that may have indicated aerogenous transmission.

- In contrast to the 2015 epornitic, more backyard farms were infected in 2022 suggesting widespread dissemination of virus by migratory birds and possible infection of domestic bird species and small mammals.

- Backyard flocks that were infected, effectively served as sentinels and were not associated with lateral transmission of HPAI to commercial farms.

- Incubation periods extending from introduction of infection to confirmation of a diagnosis were quantified denoting differences among species. This was not of direct benefit to preventing infection but could be valuable information for additional epidemiologic investigations.

It is evident that field sampling of free-living birds concentrated on migratory anseriforms. Sampling of relatively low number of birds other than waterfowl was based on the availability of clinically affected and dead free-living birds submitted to diagnostic laboratories. Raptors were in all probability infected by predation or consumption of dead anseriforms. Structured field survey of passeriformes and other families that may have been involved in dissemination of H5N1 virus were apparently not conducted since there is little mention of this aspect in the report. Although the APHIS document makes mention of infection in mammalian species, this aspect of the epidemiology of HPAI was not subjected to any structured evaluation.

It is evident that field sampling of free-living birds concentrated on migratory anseriforms. Sampling of relatively low number of birds other than waterfowl was based on the availability of clinically affected and dead free-living birds submitted to diagnostic laboratories. Raptors were in all probability infected by predation or consumption of dead anseriforms. Structured field survey of passeriformes and other families that may have been involved in dissemination of H5N1 virus were apparently not conducted since there is little mention of this aspect in the report. Although the APHIS document makes mention of infection in mammalian species, this aspect of the epidemiology of HPAI was not subjected to any structured evaluation.

The section on risk factors merely listed a series of events prior to the recognition of outbreaks. There was no attempt to determine the relative risk associated with specific activities for the large egg-production complexes that represented the bulk of losses and expediture. The Report is abysmally deficient in its failure to differentiate among commercial operations that were affected. It is obvious that risk factors relating to contract turkey-growing farms in the Dakotas are vastly different to the structural and operational factors that may predispose to infection in-line egg production complexes with over a million hens in Iowa or Colorado. For example, 53 of the 88 responses noted feed delivery within 21-days prior to detection. Why did 35 farms apparently not receive feed for 21 days? Large complexes are essentially self-sufficient with respect to feed with on-site mills. Did these units represent the non-recipients of delivered feed? Combining available data into a table that listed 46 activities was effectively a meaningless exercise. How possibly could a list of proportions be of any value in assessing risk for widely different poultry enterprises and specifically address the need to develop appropriate preventive measures?

|

Concentration on the first twelve large egg production complexes and the first twelve turkey growing farms, applying a case-control approach would have been productive. This would have required more specific and relevant Initial Contact EPI Report forms allowing the collection of data to be subjected to subsequent statistical analysis. A one-size-fits-all EPI Report questionnaire represents an oversimplification and denotes a lack of familiarity with the operations under investigation. An approach that neglects differentiation of types of poultry operation predicates failure to identify applicable risk factors.

Poultry health professionals are aware of outbreaks in farms with superlative structural and operational biosecurity. There is a gathering presumption based on informed anecdotal reports and observations that HPAI may have been introduced into large egg production complexes by the aerogenous route. This especially the case in Weld County, CO. and Buena Vista County IA. Newcastle disease most certainly can be transmitted over at least a mile as demonstrated in the Essex 1972 outbreaks in the U.K. Accepting that the infection can be acquired from the local environment including introduction on dust and soil entrained by high winds appears to be beyond the current perception of APHIS and contrary to their playbook. From the onset of the initial outbreaks, APHIS should have investigated the probability of aerogenous transmission.

The report does not address the possibility of infection of passeriform birds and their potential role in disseminating virus. The possible involvement of both domestic birds and aerogenous infection were raised during the 2015 epornitic and APHIS should have been prepared to evaluate these routes of infection from March 2022 onwards.

The modeling of avian influenza transmission and the analysis of eBird and BirdCast migration data are interesting but heuristically academic. There are neither conclusions nor recommendations advanced in the report arising from these studies that could be applied to reduce the probability of infecting commercial flocks. It is self-evident that the risk of infection in commercial and backyard farms relates to the quantum of migratory waterfowl that are shedding virus. What is required is an indication of the mechanisms by which virus passes from wild birds to farms in order to implement preventive action.

As a practicing poultry health professional, this commentator is deeply disappointed in the inability of APHIS to plan and execute a series of relevant epidemiologic studies of an infection attaining catastrophic proportions. The 2022 epornitic has cost the public and private sectors in excess of $2 billion to date without achieving control and with eradication an unattainable aspiration. Based on the consumption of 288 eggs per capita and a price differential due to HPAI of $2 per dozen, the incremental cost to consumers for table eggs and liquids was close to $15 billion during 2022. The magnitude of losses associated with HPAI should be reflected in a commensurate effort to understand the epidemiology of the infection and develop appropriate, preventive measures. Little appears to have been achieved in this respect since 2015.

What is not included in the backdated report is the reality that HPAI is now seasonally and regionally endemic in the U.S. Recognition that the infection may be transmitted by the aerogenous route negates a great deal of the accepted structural and operational biosecurity procedures promoted by APHIS and exercised by most segments of the poultry industry with varying efficiency. The 2022 epornitic highlights the vulnerability relating to conceptual biosecurity. Large egg-production complexes with two to six million hens are concentrated in areas along flyways that attract migratory waterfowl. The heightened risk has now become evident as migratory birds are disseminating a novel strain of avian influenza virus of extreme pathogenicity and wide species infectivity. Given these realities limited application of effective vaccines should be considered and evaluated for long-lived breeding and egg-production flocks at risk by virtue of location or probability of infection.

The APHIS Report confirms an obvious lack of involvement and deficiencies in conceptual planning and imagination by APHIS administrators. It is evident that they have concentrated on reacting to HPAI requiring rapid diagnosis followed by depopulation and disposal, both essential activities. Reading into the report suggests failures in proactive activities including motivation of USDA scientists, providing funding for molecular and field epidemiologic studies and cooperation with academia and industry. Basically APHIS has failed the U.S. poultry industry by neglecting to address the critical questions of what risk factors are contributing to infection of diverse commercial operations and what practical cost-effective and appropriate measures can be applied to reduce the probability of exposure of flocks.

The virus has changed, the epidemiology has changed but APHIS has not adapted to realities. The Agency is slavishly following a pre-1984 approach that would probably have been effective in stamping out an exotic infection in a limited area introduced by a single illegal importation of a contaminated product. Circumstances change but administrative mindsets are refractory to realities that are discordant with their established doctrine.

The backdated July 2022 Interim Report apparently rapidly assembled in response to industry pressure reflects an inability by APHIS to appreciate the magnitude of the 2022 (and ongoing) HPAI epornitic and its impact on the poultry industry and consumers. It is questioned as to what planning and forward thinking emerged from the 2015 epornitic? Obviously APHIS is just better at diagnosing outbreaks due to advances in PCR technology and more efficient in depopulating farms and disposing of dead birds. As an industry we deserve better!

As with all editorials USDA-APHIS Administrators, poultry health colleagues and producers are welcome to respond. Constructive responses and suggestions will be posted for the benefit of subscribers.